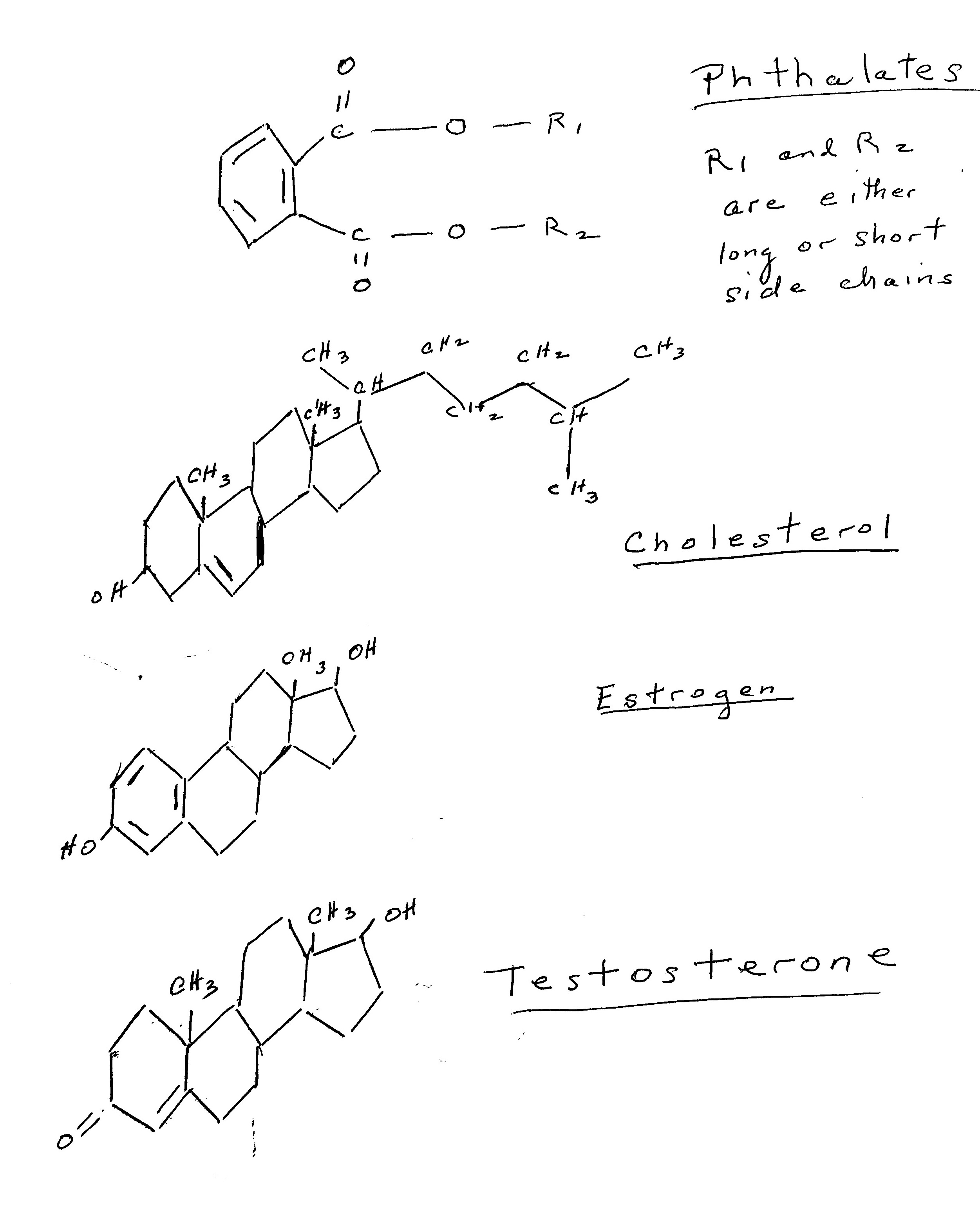

Phthalates are odorless, slightly yellow oily chemicals that are somewhat soluble in water. Basically, they are a benzene ring with dialkyl, alkyl or aryl side chains. The longer the side chains the higher their fat solubility. Phthalates are used to make plastics more durable. They are in solvents, lubricating oils, soaps, hair sprays, shampoos and many other products. Phthalates are everywhere. They are grouped into two types, based on their molecular weight and length of their side chains. Long chain, high molecular weight phthalates are used to synthesize polyvinyl chloride while short chain, low molecular weight phthalates are used in the manufacture of personal care products, cosmetics, solvents and adhesives. The environment is contaminated by phthalates and they are in our soils, drinking water, the air we breathe and dust. The food we eat can also contain phthalates. We inhale them and they also get into our bodies through our skin. Low molecular weight phthalates enter the human body primarily through skin contact while high molecular weight phthalates are ingested. In the body phthalates are metabolized and these metabolized chemicals are capable of a great deal of damage. Phthalates are eliminated by the kidneys and thus their presence can be measured in urine. The environmental phthalate may be excreted, but the metabolites are often still in the body for a longer time. They can cross the placenta from pregnant person to the human embryo and fetus.

Phthalates affect all aspects of the formation, secretion and action of the sex hormones. Cholesterol is the precursor molecule for the sex hormones. Sex hormone secretion is regulated by the interaction of the hypothalamus and pituitary glands and the gonads or the HPG axis as the highly orchestrated biochemical interaction is called. Specific hormones from the hypothalamus and pituitary are secreted by these organs. Once a hormone is secreted it binds to a transport protein and is carried through the blood stream to the target organs, which in the case of reproduction are either the ovaries or the testes. In each step of this process, phthalates will influence the normal physiological pathways of the secretion and action of sex hormones, Other processes essential to normal reproduction are affected as well. By looking at the chemical structures of cholesterol, estrogen, testosterone and generic phthalates it is easy to observe their similarities and why phthalates are called endocrine disruptors.

Numerous studies in both the laboratory using cell and tissue culture and animal models and epidemiological studies of human populations demonstrate that phthalates induce reproductive disorders. They do so by modifying the HPG axis and by interfering with cell and membrane receptors, cell signaling pathways as well as by the modulation of gene expression.

Phthalates target Sertoli and Leydig cells of the testes and have been shown to cause a decrease in sperm motility and to damage sperm. They are known to cause testicular dysgenesis syndrome. In this condition the testes are smaller than usual, weigh less and demonstrate impaired spermatogenesis. Phthalates have also been shown to cause the congenital abnormalities of hypospadias (abnormal urethra opening along the penis) and cryptorchidism (undescended testicles). Getting to the understanding of how phthalates influence reproductive organs, is tricky. It seems that the timing of phthalate exposure, the concentration of the phthalate, the chemical structure of the phthalates affects the outcome. Furthermore, there are numerous types of phthalates and all contaminate the environment so that it is almost impossible to determine how one specific phthalate causes reproductive tract alterations. For instance, studies in boys show that phthalates can delay puberty, or cause early onset puberty. Further well designed and conducted studies are necessary to sort out the details of just exactly how phthalates affect males. Puberty in females is also delayed in some cases of phthalate exposure, but this exposure is also reported to cause early puberty, particularly in obese girls. In females, phthalate exposure has been reported to decrease oogenesis and reduce ovarian reserve as well as induce premature ovarian failure. During pregnancy the phthalate metabolites have been shown to cause spontaneous abortion (miscarriage) and preterm birth. Phthalates also are known to lead to ovarian and cervical cancers.

Uterine fibroids are a serious condition that affects 70 to 80% of women and recently were a focus or the Campion Fund. Thus, it was of interest to read several recent studies on the topic of phthalate exposure and possible association with fibroid initiation and growth. One retrospective study suggested that indeed there is an association. This reported study of 754 women aged 45-54 years of age from Baltimore, Maryland and adjacent areas analyzed the self-reported past diagnosis of fibroids with the levels of nine phthalate metabolites in pooled 1-4 urine samples. The authors of this paper, Nowack, Bulun and Flaws and colleagues, reported a 13% increased risk of uterine fibroids for every 2-fold increase in two of the nine phthalate metabolites, di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and anti-androgenic phthalate. They also reported that women who were overweight from age 18 to their age at the time of study showed a stronger association of phthalate exposure to the past fibroid diagnosis. The authors mention in the discussion that the study was not designed originally to detect uterine fibroids.

On the other hand, a prospective case-cohort study of a subset of Black premenopausal women aged 23-35 found that higher urine concentration of phthalates and phthalate alternatives was not associated with an appreciable high risk of development of uterine fibroids. The authors, Baird, Wise and colleagues conducted the study in Detroit, Michigan. This prospective study was designed to determine the incidence of fibroids by vaginal ultrasounds. The 754 subjects were followed over time and urinary concentrations of fourteen phthalate metabolites and 2 phthalate alternative plasticizers were obtained at baseline, 20 months and 40 months from baseline.

The fact that the study that reported no association was a prospective study that was designed to determine the incidence of uterine fibroids gives great credence to the fact that phthalates are not associated with an increased risk of the development of fibroids. Another argument that supports this conclusion is that uterine fibroids have been reported as a serious condition over many centuries at a time when phthalate contamination of the environment did not occur. However, researchers will need to conduct additional studies to confirm the findings. Nevertheless, it does seem prudent to be concerned that phthalates might influence our reproductive health.

References

Hlisníková H, Petrovičová I, Kolena B, Šidlovská M, Sirotkin A. Effects and Mechanisms of Phthalates' Action on Reproductive Processes and Reproductive Health: A Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Sep 18;17(18):6811. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186811. PMID: 32961939; PMCID: PMC7559247.

Iizuka T, Yin P, Zuberi A, Kujawa S, Coon JS 5th, Björvang RD, Damdimopoulou P, Pacyga DC, Strakovsky RS, Flaws JA, Bulun SE. Mono-(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate promotes uterine leiomyoma cell survival through tryptophan-kynurenine-AHR pathway activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022 Nov 22;119(47):e2208886119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2208886119. Epub 2022 Nov 14. PMID: 36375056; PMCID: PMC9704719.

Pacyga DC, Ryva BA, Nowak RA, Bulun SE, Yin P, Li Z, Flaws JA, Strakovsky RS. Midlife Urinary Phthalate Metabolite Concentrations and Prior Uterine Fibroid Diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Feb 26;19(5):2741. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19052741. PMID: 35270433; PMCID: PMC8910544.

Weuve J, Hauser R, Calafat AM, Missmer SA, Wise LA. Association of exposure to phthalates with endometriosis and uterine leiomyomata: findings from NHANES, 1999-2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2010 Jun;118(6):825-32. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901543. Epub 2010 Feb 25. PMID: 20185384; PMCID: PMC2898860.

Fruh V, Claus Henn B, Weuve J, Wesselink AK, Orta OR, Heeren T, Hauser R, Calafat AM, Williams PL, Baird DD, Wise LA. Incidence of uterine leiomyoma in relation to urinary concentrations of phthalate and phthalate alternative biomarkers: A prospective ultrasound study. Environ Int. 2021 Feb;147:106218. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106218. Epub 2020 Dec 21. PMID: 33360166; PMCID: PMC863074